Thursday, April 14, 2011

What I Learned From The Last 25 Best Original Screenplay Winners

So you want to write an Oscar-winning screenplay. Well, I thought I’d have a little fun this week and look back at the last 25 Oscar winners in the best Original Screenplay category and see if I can’t lock down a pattern or two as to what kind of script wins this most prestigious of competitions. If this is, indeed, a collection of the best writing over the past 25 years, it wouldn’t hurt to figure out what these writers are doing. So below, I’ve listed the last 25 Oscar Winners in order (from 1986 to 2010) and afterwards, I’ll share with you nine observations I found from combing through the list. Your Oscar winners ladies and gentleman…

1986 - Hannah and Her Sisters (Woody Allen)

1987 – Moonstruck (John Patrick Shanley)

1988 - Rain Man (Ronald Bass and Barry Morrow)

1989 - Dead Poets Society (Tom Schulman)

1990 – Ghost (Bruce Joel Rubin)

1991 - Thelma and Louise (Callie Khouri)

1992 - The Crying Game (Neil Jordan)

1993 - The Piano (Jane Campion)

1994 - Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino and Roger Avary)

1995 - The Usual Suspects – Christopher McQuarrie

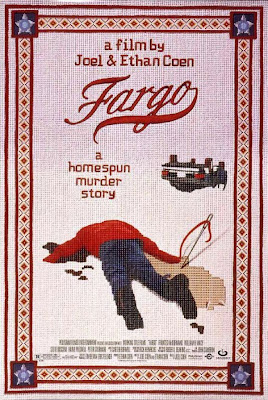

1996 – Fargo (Joel and Ethan Coen)

1997 - Good Will Hunting (Matt Damon and Ben Affleck)

1998 - Shakespeare In Love – (Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard)

1999 - American Beauty (Alan Ball)

2000 - Almost Famous (Cameron Crowe)

2001 - Gosford Park (Julian Fellowes)

2002 - Talk to Her (Pedro Almodovar)

2003 - Lost In Translation (Sophia Coppola)

2004 - Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind (Pierre Bismuth, Michael Gondry, Charlie Kaufman)

2005 – Crash (Paul Haggis)

2006 - Little Miss Sunshine (Michael Arndt)

2007 – Juno (Diablo Cody)

2008 – Milk (Justin Lance Black)

2009 - The Hurt Locker (Mark Boal)

2010 - The King’s Speech (David Siedler)

DISPARITY

First thing I noticed about the Oscar winners is how much disparity there is in the genres. We start with an ensemble comedy, move to a romantic comedy, then to a road trip buddy drama, then to an inspirational teacher movie, then to a supernatural romantic drama. Our most recent five are a “wacky family” movie, a teenage comedy-drama, a gay rights leader biography, a war film, and a period piece. Naturally, my first inclination is to say, “There are no patterns in this! The Academy just picks whatever the best script is that year.” Kinda cool. But wait, I looked a little deeper and, what do you know, I was able to find some commonalities…

DRAMA!

Fifteen of the 25 scripts listed are dramas. That’s an even 60%. This would make sense, as drama is the genre most reflective of real life and therefore the vessel most likely to put us in touch with our emotions. Unlike thrillers and horror and action movies, which take us to places we’ll never go in our real lives, drama places a mirror up to us and says, “Hey, this is you buddy.” From losing your job like Lester Burnham in American Beauty to taking a stand for an issue you believe in like in Milk. This is the most affecting genre in film when done right, so naturally, it’s going to result in some of the most affecting films. Now while this DIDN’T surprise me that much. The next trend I saw did. Because this is the last thing you’d expect the Academy to celebrate….

HUMOR!

The Academy has a bad rap for not recognizing comedies the way they do other genres. But take a look at the movies on this list. Almost all of them make you laugh. Sure, most of the time, the humor is dark, but Almost Famous, Rain Man, Moonstruck, Pulp Fiction, Ghost, Fargo, Good Will Hunting, Juno, Crash, Eternal Sunshine, Little Miss Sunshine. There is a lot of humor in those movies. This is a huge revelation for me. Because when you think of the stodgy Old Guard that is the Academy, you think you have to go all drama all the time. This proves that infusing your script with comedy, albeit balanced with drama, is just as important.

DON’T BE AFRAID TO ENTERTAIN

One thing I expected to find when I pulled this list out was something akin to the Nichol Winner choices - since they’re operating under the same umbrella – scripts that specifically focused on a deeper element of the human condition (and I did find a few: Milk, The Hurt Locker). But I was surprised at just how many films wanted to entertain you. Juno, Fargo, Gosford Park, Pulp Fiction, Ghost, Almost Famous, The King’s Speech. These movies just want you to have a good time in the theater first, AND THEN if you want to look deeper, they serve you an extra helping of warmed up leftovers to dig into later. I think when people sit down and think, “I want to write an Oscar screenplay,” they get into this mentality that they have to change the world with every word. But there’s enough of an entertainment factor to all these movies that I think the old saying, “Entertain first, teach second,” is the way to go.

THERE’S AN ELEMENT OF LUCK TO WRITING A SCREENPLAY

One of the scariest realizations I had going over this list is that there is a huge amount of luck involved in writing a great screenplay. And I don’t mean that writing doesn’t require skill. What I’m saying, rather, is that sometimes a story just comes together and sometimes it doesn’t. And we don’t always know if it’s coming together until we’re well into writing it. I say this because in the last 25 years, there has been a different winning screenwriter in the original screenplay category every single year. And there is only one writer (or pair of writers) who have won twice if you include the adapted category, and that’s Joel and Ethan Cohen for both Fargo and No Country For Old Men. You would certainly think that, if you’re good enough at your profession, you would continue to win at least somewhat consistently over the course of your career. But the opposite is true in this category. What this tells me is that the screenplay is the star, not the screenwriter, and I don’t say that to diminish the work of the writer, but rather to remind you, if you come up with a good idea that seems to be working on the page, nurture that thing and make it the best you possibly can. Because like it or not – even for the best screenwriters – the great idea combined with the perfect execution just doesn’t come around very often.

LEARN TO DIRECT

Nine of these winners directed their screenplays. That’s 36%. Although I sometimes question the writer-director approach (writer-directors may be too close to the material to be objective), it’s clear from this number that the approach pays off. This is probably because directors write with a director’s point of view, which is a little different than a writer’s point of view. They can visualize cinematic sequences they know will work, whereas a screenwriter might know that sequence will read terribly on paper and ditch it. Take the 12 minute dialogue scene in Jack Rabbit Slim’s in Pulp Fiction for example. That would never survive in a spec script. The producers would scream foul at a 12 minute dialogue scene with 2 people sitting at a table. But Tarantino can visualize the setting, the characters, the mood, the tone, and know it will work. This freedom allows the writer-director to write things differently, and the Oscar-voting crowd likes rewarding things that are different.

TRENDING TOWARDS THE SINGLE PROTAGONIST

A lot of these winners consist of an ensemble cast (American Beauty, Crash, Gosford Park, Little Miss Sunshine, Fargo, Hannah and Her Sisters, Pulp Fiction). Cutting back and forth between multiple storylines seems to get the Academy’s juices flowing. However, I noticed that the past four winners more or less follow the traditional singular hero journey that is so often taught by screenwriting books and gurus. They may not be executed on the same basic level as Liar Liar or Taken, but the single hero journey it is. So don’t feel like you have to populate your story with multiple characters and multiple intersecting timelines to get the Academy’s attention. You can follow just one guy. Just make sure that guy is interesting!

NEVER FORGET THE POWER OF THE IRONIC CHARACTER

Robin Williams is a therapist who doesn’t have his shit together. Matt Damon is a janitor who’s a mathematical genius. Dustin Hoffman is a mentally challenged man who’s a genius at black jack. Colin Firth plays a king who’s unable to speak to his people. Audiences are fascinated by ironic characters, those who are in some way opposite from the image they project. These characters are by no means necessary to write a great script, but if you can work one into your story, it’s going to make you and your script look a lot more clever, which should give you a bump come Oscar time.

TAKE HEED LOW-CONCEPTERS

For those of you out there worrying that your script is too low concept, you might want to toss your hat in the ring for an Academy Award. Truth be told, very few of these loglines scream “I have to read this now!” The exceptions might be Ghost, Rain Man, Eternal Sunshine, and Shakespeare In Love. However, it’s important to remember that almost everyone on this list had a previous level of success in the industry which guaranteed that their screenplay would get read by others. Who knows how long these great scripts might have sat on a pile unread because the loglines were average and they were written by Joe Nobody. So I still think the best roadmap to success is to write that high-concept comedy or thriller first, THEN bust out your multi-character period piece about a prince suffering from whooping cough second, in order to snatch that Oscar you so richly deserve.

So, that’s what I found. Did I miss anything? I noticed that a lot of these scripts were written by a single person as well, so time to dump your writing partner (kidding). I still feel like there’s a magical formula here as there definitely seems to be a similarity with all these scripts that I can’t put my finger on. So I’ll leave that up to you. Enjoy discussing.